From their book are we human?, Beatriz Colomina and Mark Wigley define design as

defense. Most theories of design present the human as under some kind of threat that needs to be urgently countered by design. The defense is seen to draw from some quality deeply embedded in the human, as if design itself is the natural human way to preserve the human. The most radical attempts to reshape the human are typically carried out under this guise of reinforcing and protecting the human. Design is a paradoxical gesture that changes the human in order to protect it.

This definition, although never stated in such a critical manner, is most often considered “good design” within the disciplines of design because it’s never challenged to be any other way. But Swati Piparsania’s work does the opposite of Colomina and Wigley’s definition and that’s why her work is so vital. Rather than protect humans, her designed objects expose humans for who they are, and this vulnerability leads to a discourse in which users—rather than designers—lead the discussion about what is needed, what is wrong, and what is useful in our lives. In a way, Piparsania’s objects make room for each of us to be wrong, giving us opportunities to reflect on how we each participate in our world’s built environments.

While Piparsania’s work may lack conclusive or detailed scientific research, her work is still rooted very much in reality because it is based on what we all survey in this world and either have become oblivious to or believe we don’t possess the means to make a change. Yet her objects are also fictional because, like any great work of fiction, they spark the imagination within a user to reframe or rethink what could be done with something so inconceivably wrong. Furthermore, unlike most designed products that are marketed as necessities, Piparsania’s objects are participatory, letting you decided how you want to behave rather than modernist and Silicon Valley ethos and systems telling you how to feel or do something.

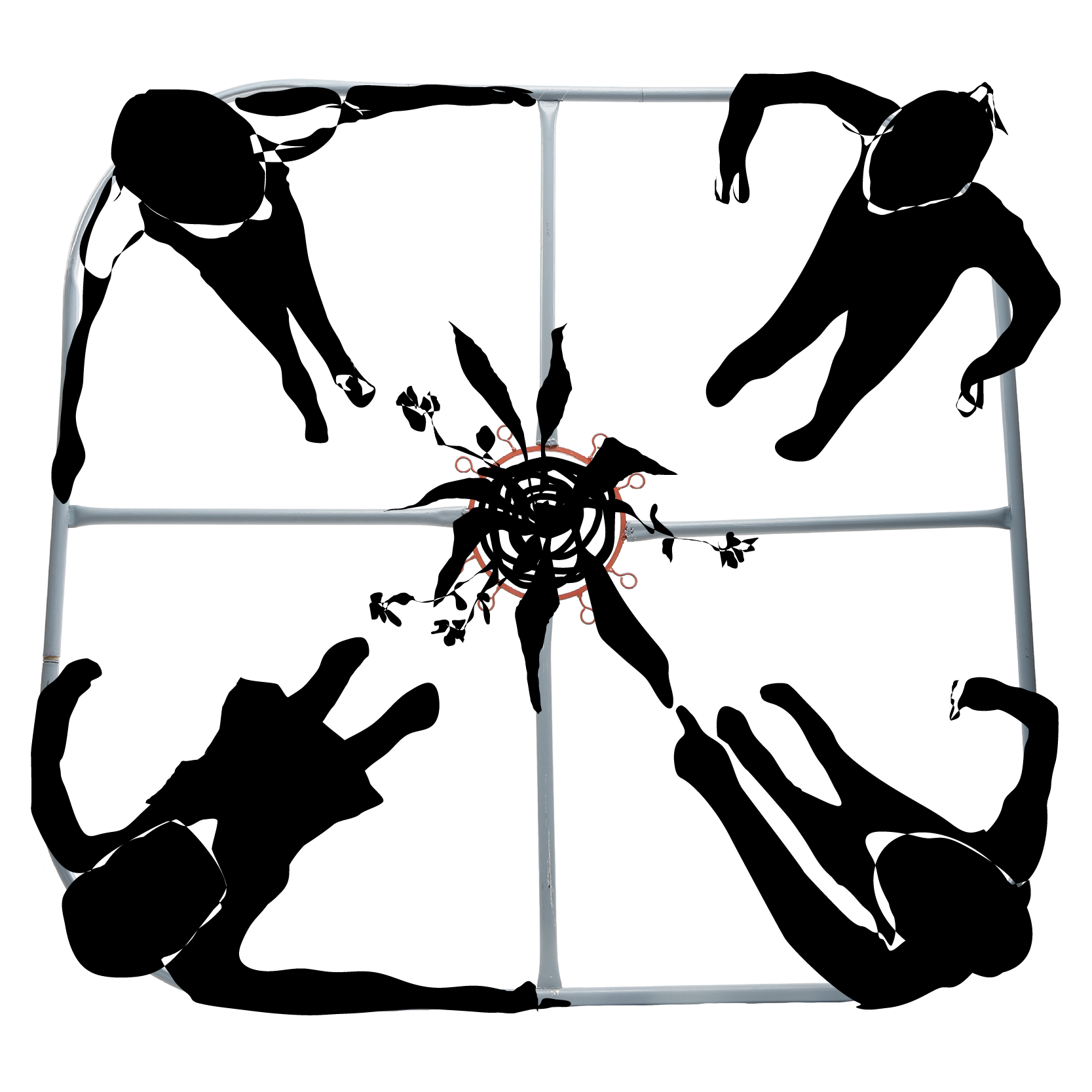

Author Ursula Le Guin, known for her fictional writings, once remarked that “all of us have to learn how to invent our lives, make them up, imagine them. We need to be taught these skills; we need guides to show us how. If we don't, our lives get made up for us by other people.” Piparsania’s Gridded Walking object is one such guide for us to fulfill our lives, as Le Guin states, in a constant inventive and imaginative way. The object allows up to four standing users to bear their weight against four quadrants of the object to create a mobile conversation pit (the potted plant as a centerpiece also helps to brighten the mood)—nothing needs to be held, and only the conversation of the four users can guide the entrapped group in a new direction. But it’s not until you’ve used Gridded Walking that you realize how it reverses our natural modern inclination to lean back and walk away from a conversation into a form of comfort, letting our egos slide off our relaxed shoulders as we giggle and embrace how we communicate to one another. It’s like a potato sack race, but with eight legs bound together and no end-goal in sight.

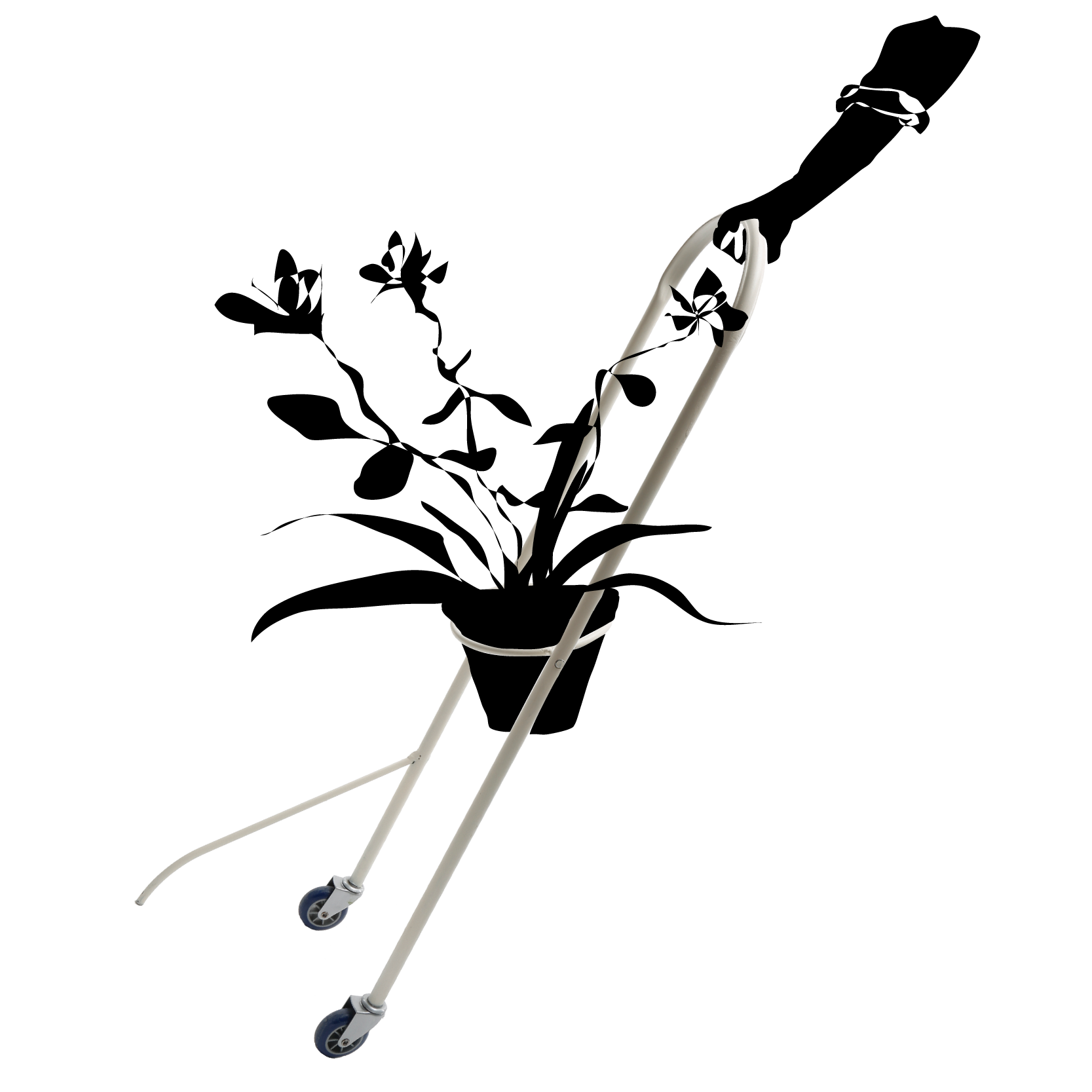

Piparsania’s Take Your Plant For A Walk object series takes Gridded Walking’s awkward moments and applies them solely to individual use cases. By taking your houseplant for a walk outside, like we would with a pet dog or even a toddler, we further let our egos and facades drop and, in a way, become confident fools. But foolishness should not be confused with ignorance because the absurdity and humor of this object and activity allow us to be open and vulnerable, leading to design conversations that aren’t about the need to protect or isolate ourselves from each other, but rather that we need to protect each other with unprejudiced compassion.

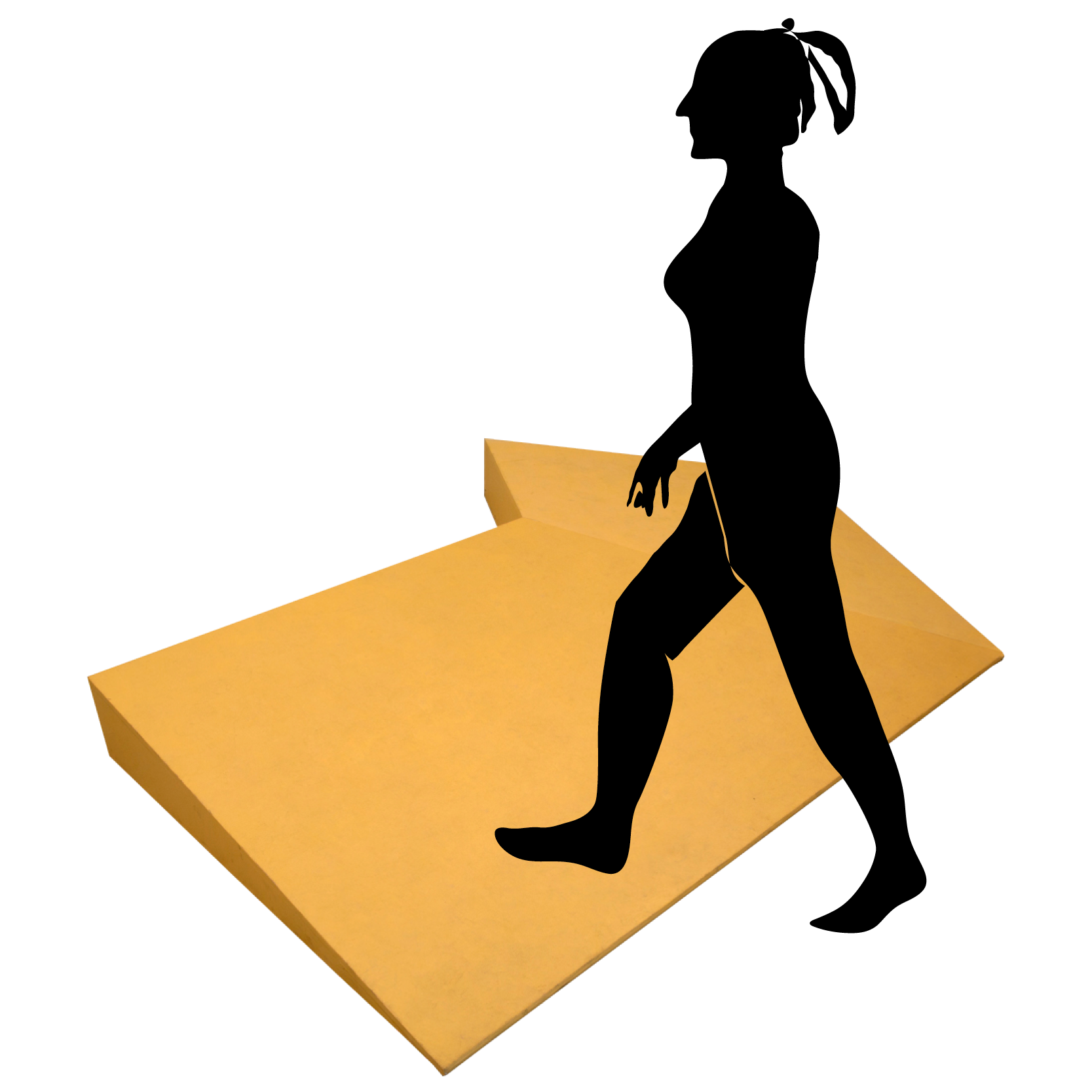

Ramps, Piparsania’s most recent work, bring these ideas of awareness, activity, and absurdity together once more. Low-level pastel pink wooden ramps liter the floors of a space and suggest that we walk upon them. They are a playground of sorts for adults—although just as much as for children—built upon an invitation of curiosity. Walking over, across, or even within these ramps, one comes to the conclusion, “Does haste really improve our lives?” As Ferris Bueller once said, “Life moves pretty fast. If you don’t stop and look around once in a while, you could miss it.” By fabricating inclined trails of the less traveled, filled with hinderances and obstructions, Piparsania is building both inspiration and resilience in how we approach the mundane, tragic, dire, and beautiful moments of our lives.

Piparsania’s objects are not representations—they are exactly as we function in spaces and in society. They critique society by letting us behave exactly as we normally would. We are not actor’s wearing these objects; we are not guinea pigs using these objects: we are ourselves, no more and no less. Moreover, and most importantly, Piparsania’s objects are more than just objects—they are a commentary not necessarily on our lives but on design’s overbearing assumption that it knows best. They are reimaginings of how we can construct the built environment around us, with laypeople’s opinions and views holding equal value to designers’ intuition.