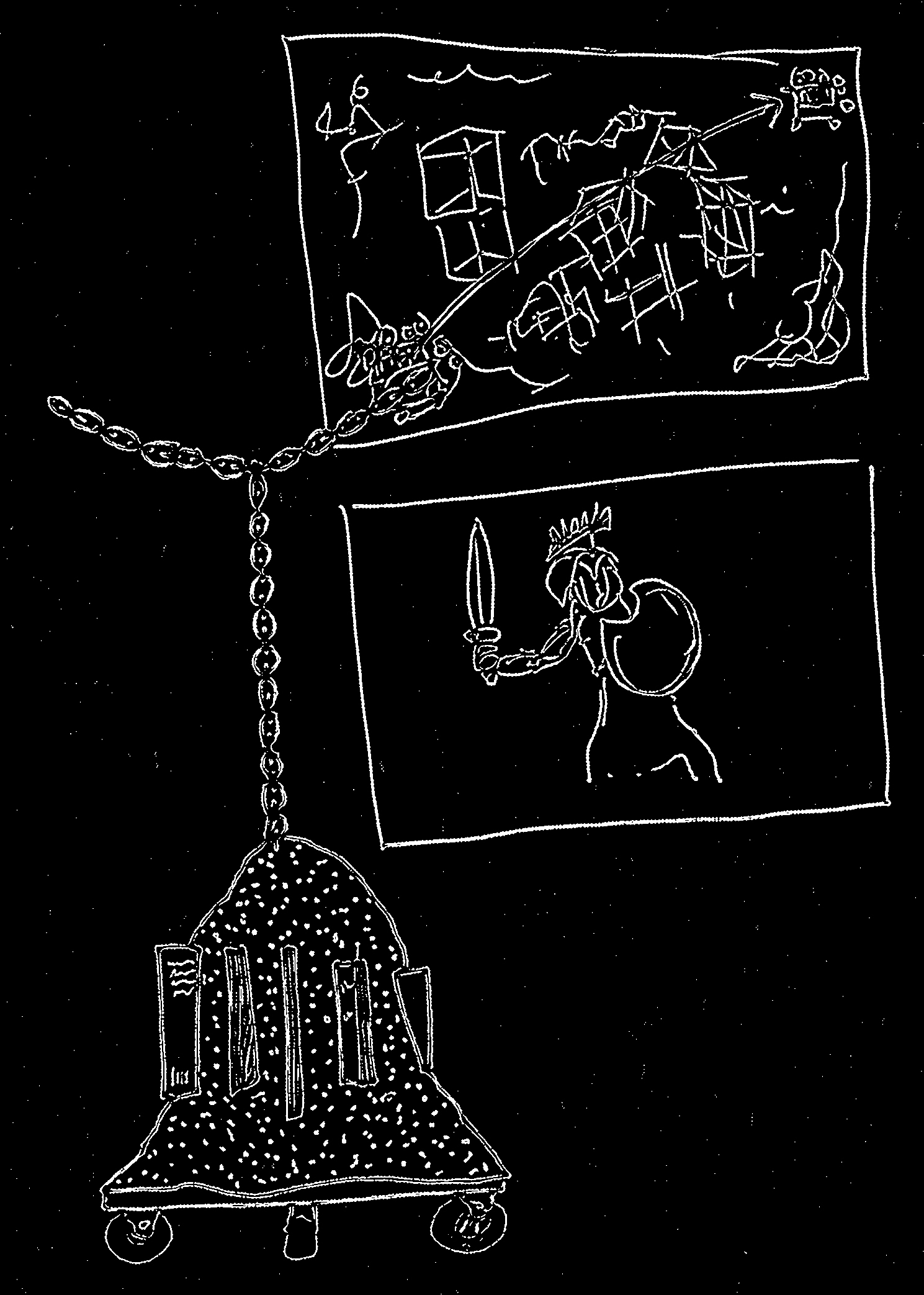

Step-brother, the mobile gallery run by Lucas Albrecht, and, in a much larger capacity than before, Sam Panter, has expanded itself with a new mobile “resource” center. With a sand dune base that contains slots for books, casters for mobility, and a welded chain shaped and stiffened into a missal/book stand, this new mobile resource center of Step-brother screams “zany” but hides something more sinister.

Like any library or resource room that is a part of an institution, it has an archive of its founding. In this case, two large sketches are hung, one above the other, near the mobile book stack and are labeled as the “brainstorming session” that lead to the creation of the book stack. However, there is something peculiar within the top sketch. It contains two separate illustration styles, one of which is whimsical and contained to the corners of the canvas, while the other style—drawings of cubic structures—disproportionately overwhelms the rest of the canvas. But it’s those smaller corner drawings that are of intrigue, one of which depicting the mobile book stack with an arrow tracing diagonally over the entire canvas and the cubic drawings of the other illustration style like a large yet thin “NO” symbol, and finally landing at the opposite corner pointing at what looks like an overflowing cart of silicone breasts. Clearly, based on the actualized mobile book stack, only one person’s vision in this “brainstorming session” was taken into consideration.

Below this drawing is a sketch of a classical Roman warrior. Maybe Spartacus? As one may or may not know, Spartacus was a gladiator who escaped his imprisonment and became a leader in the Third Servile War, which was a major slave uprising against the Roman Empire. Spartacus, over time, has been featured in literature and film as a symbol of one representing the power and leadership of the oppressed. Even communism and Karl Marx have used Spartacus as an icon for their politics, referring to Spartacus as an “ancient proletariat.” However, Spartacus and his rebellious army of oppressed were eventually killed by the Roman empire…but maybe that’s exactly why this drawing was chosen to represent one half of this gallery’s partnership.

And as the old adage goes, “history repeats itself,” so it’s not difficult to see how the mobile book stack continues the trend of power that this partnership has promoted. Step-brother, the larger entity and gallery space that this new resource center belongs to, was proclaimed to be an all-inclusive gallery that would cater to all artists and designers that needed representation within a space. However, on it’s inaugural opening, Step-brother and its curators/owners distinctly left out one new-to-the-scene artist. Now, this new mobile book stack presents itself as a “collection of resources for Step-brother” (emphasis mine), meaning, unlike a library, either public or as a division of an institution, it does not promote knowledge exchange. Furthermore, the construction of this book stack deters you from even viewing the books shoved into the slots of its sand dune base. For one, these slots are formatted to fit only the books of Albrecht and Panter’s choosing. For a gallery that’s supposed to be ever-evolving in the artists and themes it exhibits, it’s ethos continue to embrace exclusivity. Will not some future conversation that Albrecht and Panter have with some patron or potential artist/designer influence the future of Step-brother and its collection of resources? I guess not. Secondly, when one tries to pull out some of the books in the collection, they find that the slots were carved too tight around the books. As one tries to wiggle the book out, the painful sounds of sand rubbing against this precious collection dissuades them from trying to force the book out of its slot. (In some cases, you can’t even wiggle the book. What a tease!) If you do manage to get one of the books out, getting it back in is just as troublesome as corners of the books and their pages bend, curl, and once again rub abrasively against the sandy slots. (It seems that Albrecht and Panter are certainly not ones for preservation.) In a way, it’s a bit like Gustav Metzger’s auto-destructive artworks, but where Metzger was trying to replicate the destruction of war through his work, Step-brother and its “fathers” seemingly want to destroy each others influences for the sake of…something.

Also, the selection of books is very self-referential. The trendy curation of graphic design, publishing, and exhibition theory books (with a slight DIY twist to some of the titles) hit too close to the actual structure and self-proclaimed intentions of Step-brother and its resource center, both structurally and conceptually. As if trying to replicate something found in All Possible Futures, one of the books in its collection, this resource center ends up being nothing more than an aesthetic take on “zany” and consequently references the late 1990s children’s television program Teletubbies: the bright yellow metal chain book stand, extruding from the top center of the sand dune base, zigzags like the antennas of the Teletubbies, and the oddly dark green sand dune, with books in its base, mimics the communicative television screens in the Teletubbies’ abdomens. But, as stated earlier, Step-brother is built on exclusivity, so the major theme of the Teletubbies—the wonder and surreal charm that cooperation can bring about—is sorely lacking in the resource center. Also, you can’t build a (cult) following, as the Teletubbies did with adolescent and college-age audiences, when everything refers back to it’s overbearing owners rather than the potential of where the curated collection of books and interests can lead to. Finally, one of the books on display is about grooks, “a short aphoristic poem, accompanied by an appropriate drawing, revealing in a minimum of lines some basic truth about the human condition.” This resource center could be seen as a physical representation of a grook, with its collection of books as the poetry and the hung sketches as the neighboring representative drawings, but the only “basic truth” this resource center reveals is that it’s built upon buzz words and power—a symptom of its owners caring too much about how they and Step-brother are perceived rather than how it contributes to a scene.

Which leads me to what I’ve been alluding to this whole time—the sinister element that I mentioned at the beginning. Let’s begin with the two styles of the historical “brainstorming” sketches. Step-brother, originally Albrecht’s concept, is a mobile, cubical module gallery, and this cubic thinking was what prominently filled the top sketch of the new resource center. But again, this cubic thinking was slyly crossed out by the whimsical style of the corner illustrations that depicted the mobile book stack and the cart full of breasts it points to. If Albrecht drew the cubic drawings—representative of his original Step-brother concept—then Panter is the author of the whimsical corner drawings that subliminally call Albrecht a boob for following through on building Panter’s vision of Step-brother’s resource center. Albrecht, realizing this revolt in ownership of Step-brother, is then depicted as Spartacus, alone in the void of a blank canvas for all patrons of the gallery to mock. And, as you may remember, Spartacus and his rebellion are ultimately defeated, killed, and crucified. It’s worrisome that the fall of the original mastermind of Step-brother is presented as a prominent power-move in this gallery’s short history.

Sadly, this resource center—or Step-brother for that matter—isn’t about its structures, books, historical drawings, or who it represents. As a whole, Step-brother is about—to use the words of Panter—systems of power, particularly systems that are built around human necessity to carry out one’s vision. Taken one step further, this has been a coup by Panter, defacing Lucas (“the boob”) Albrecht and his original plans with subtle demeaning imagery as a form of normalization (i.e., male-bonding and teasing as empathy or equity) within the partnership. But the bigger problem of Step-brother and it’s components isn’t Panter’s coup, it’s that this “community” gallery and its self-referential habits, regardless of ownership, still have guests asking, “Why should I care?” It seems like Panter (and Albrecht, if he’s still breathing) needs to go back to the brainstorming drawing board to right the course of this gallery and its intentions.